Authors

Nan Bai , Shervin Azadi , Pirouz Nourian , Ana Pereira Roders

Abstract

This paper reports the formulation, the design, and the results of a serious game developed for structuring negotiations concerning the redevelopment of a university campus with various stakeholders. The main aim of this research was to formulate the redevelopment planning problem as an abstract and discrete decision-making problem involving multiple actions, multiple actors with preconceived gains and losses with respect to the comprising actions, and decisions as combinations of actions. Using fictitious and yet realistic scenarios and stakeholders as simulation, the result evidences show how different levels of democratic participation and different modes of moderation can affect reaching a consensus and present in a mathematical characterisation of a consensus as a state of equilibrium. The small set of actions and actors enabled a chance to compute a theoretically optimal state of consensus, where the efficiency and the effectiveness of different modes of moderation and participatory rights could be observed and analysed.

Presentation

Overview

The objective of the research was to frame an urban development problem as a gamified multi- actor/multi-objective social decision-making process and accordingly formulate the problem mathematically so that it can be further analyzed by means of graph theory and game theory. The biggest question in the background of the research was whether such problems can be solved computationally (at least from a mathematical point of view), and if yes, why should they be framed as games? The answer to this question is partially dependent on the scale (level of detail) and thus the complexity of the problem and to some extent on the social aspects of the problem. Our formulation shows that the order of complexity of such problems is exponential with respect to the number of objects raised to the power of a maximum number of choices available per each object. This could be a justification to apply (meta) heuristics to search for optimal outcomes. However, there may still be two reasons why both gaming and artificial intelligent methods (meta-heuristics) could be relevant at the same time: on the one hand, in case of large problems, they could be NP-hard, i.e. mathematical problems with no known algorithms for solving them systematically in polynomial time, whose solutions can only be ‘approximated’; and on the other hand, even if the solution is approximated by means of algorithms and machines, humans must be involved in formulating, understanding, and attempting to solve the problem so that they can ‘accept’ and ‘abide by’ the solution (the final decisions). In other words, the didactic use of the game and its necessity for enabling participation cannot be overruled by the use of AI methods. On the contrary, the two approaches need to be combined to make the most out of such decision-making processes, socially and scientifically.

The main contribution of the paper is proposing a formal (mathematical/computational) formulation of a ‘wicked-problem’. The analyses performed on the proceedings of the games show that designing such games and playing them can help diverse groups reach consensus more efficiently.

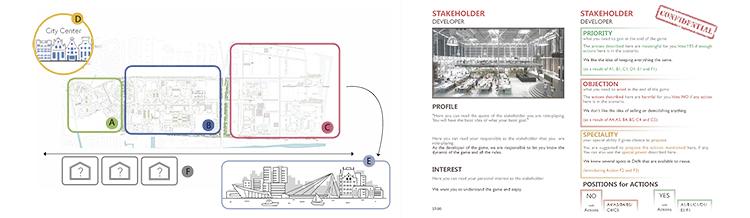

Example of the game interface during the workshop. Left: the sites to decide on. Right: The stakeholder profile declaring the preference type of each agent.

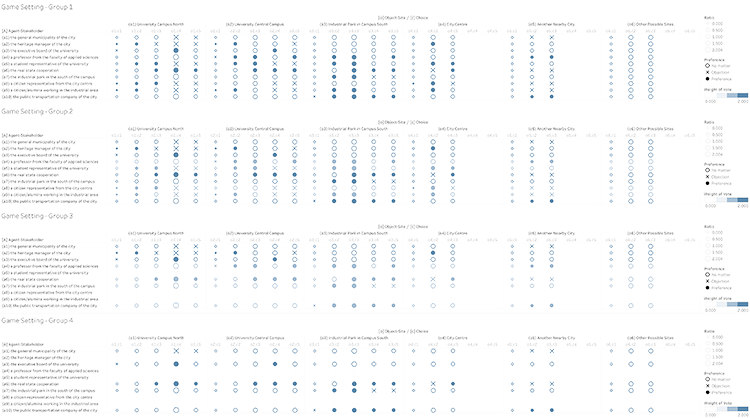

Records of the gameplay in the workshop.

The decision made by each group within each group are shown as polygons, whose vertices are the chosen choices per each object (coloured groups). The height of the coloured bars indicates the potential social benefit of each choice per object. Hexagons are slightly offset inwards and coloured differently so as to distinguish different rounds of the games.

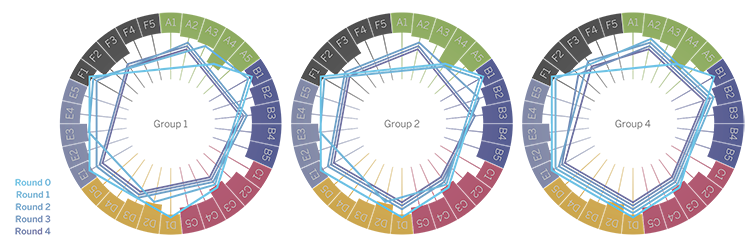

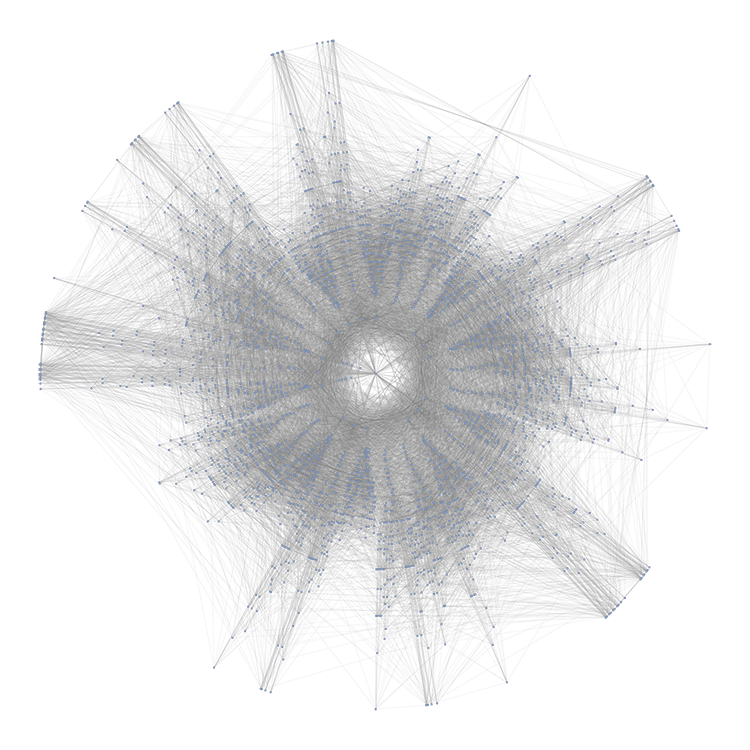

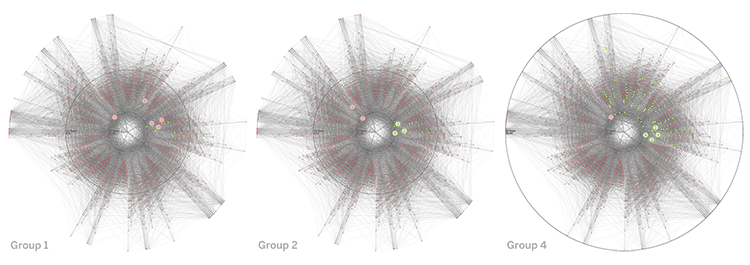

The embedding of the decision graph in the polar coordinate system. To create this embedding, we map the index of each decision to angular coordinates and we map the reversed social benefit of the decision to radial distance. This means that as closer the decisions get to the center of the graph, the higher their gain-cost ratio is for the society.

Green nodes are consensual decisions, and Red nodes are non-consensual decisions. Blue trajectory and the numbers indicates the progression of decision making through playing rounds for each group. Black circles highlight the bounds of gain-cost ratio for the consensual decisions.

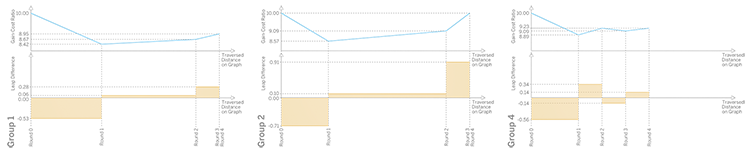

Blue line: gain-cost ratio plotted against the traversed distance, Orange Line: leap difference function against traversed path lengths per each round. After the “FIGHT” in the round 2 for group 4, the leap difference function becomes negative. It is also presented that the initial round of all groups has a negative value, which is due to the fact that they have started from a non-consensual node with 10, therefore their first step has been toward consensus, rather than maintaining the gain-cost ratio. Moreover, in the last round of all groups the leap function has a positive value.

Acknowledgement

Authors Nan Bai and Ana Pereira Roders were supported by of the HERILAND project funding (Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 813883). Authors Shervin Azadi and Pirouz Nourian were supported by the GoDesign project funding (Ontwerp en Overheid, grant agreement number AUT03G). The suggestions of anonymous reviewers are gratefully appreciated. The authors thank Maria Valese, Francesca Noardo, Azadeh Arjomand Kermani, Roberto Rocco, and Franklin van der Hoeven, for their suggestions and/or contributions for/in organizing the serious gaming workshop.